Limits

In the study of calculus, understanding the concept of a limit is a stepping stone towards delving into continuous functions, derivatives, and integrals. The formal definition, often referred to as the - definition, is important yet can initially seem impenetrable. These are my notes on the formal definition of limit aimed towards building an intuitive understanding.

Formal Definition

The formal definition of limit hinges on the notions of arbitrarily small quantities, encapsulated by Greek letters (epsilon) and (delta). Given a function , the statement

is interpreted as: for each small number , there exists a number such that if , then . In a more symbolic notation, this is articulated as:

The crux of this definition lies in the quantifiers. It's about guaranteeing that gets arbitrarily close to as approaches , by making small enough.

Dissecting the Formalism

Let's dissect the components of this definition:

- The Limit Point (): This is the point that is approaching.

- The Limit Value (): This is the value that is approaching as approaches .

- The Epsilon (): Represents how close is to .

- The Delta (): Represents how close is to .

The inequalities and are crucial as they formalize the notion of "closeness".

Bridging to Intuition

The - definition at first might seem detached from intuition. However, a geometric interpretation can provide a clearer picture.

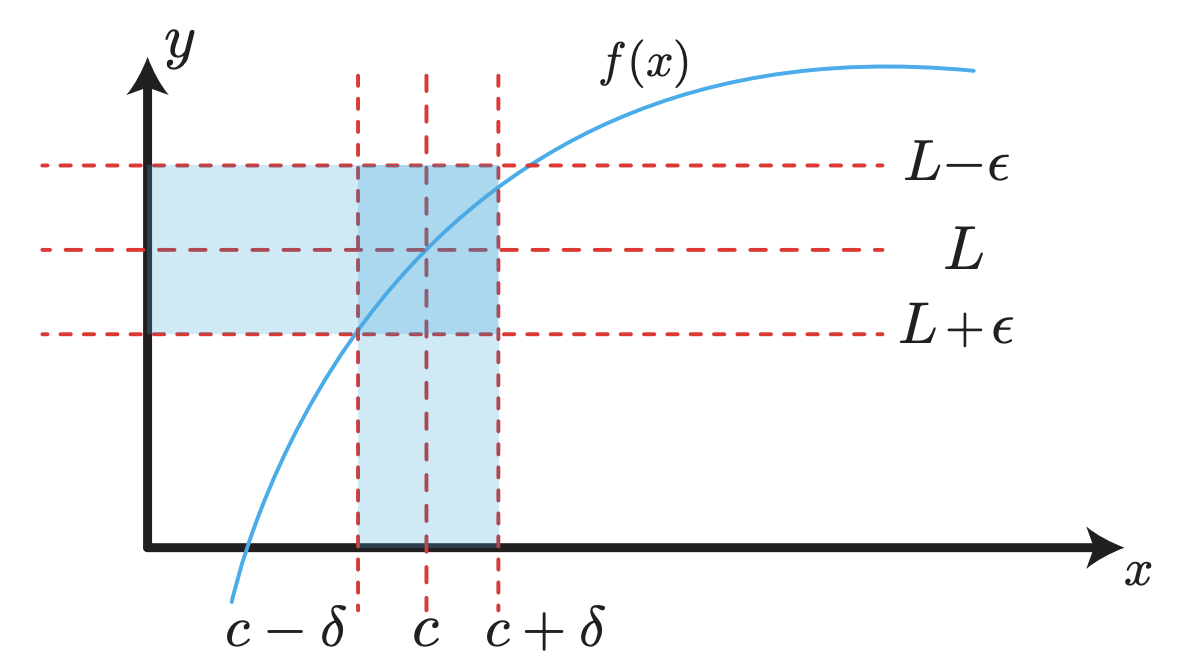

Geometric Interpretation

Imagine a graphical representation where the function is plotted against . The point is where we are focusing, and is the value that is approaching. Now, envision two horizontal lines at and . Similarly, draw two vertical lines at and . The essence of the definition is that as moves within the vertical bounds, stays within the horizontal bounds.

A figure illustrating this geometric interpretation can greatly aid in understanding. The figure would show the function , the point , the value , the and bounds, and how remains within the bounds as is within the bounds around .

Concrete Scenario

Consider a real-world scenario where a car's speedometer approaches a certain speed as the car accelerates. Though the needle might never hit the exact speed due to mechanical limitations, it gets arbitrarily close. This scenario mirrors the behavior of limits, where gets arbitrarily close to as gets arbitrarily close to .

Through this blend of formalism and intuition, the concept of limits becomes less daunting, serving as a solid foundation for further exploration in calculus.

Certainly. Here’s a section on the formal definition of a limit as ( x ) approaches infinity:

Limit as ( x ) Approaches Infinity

In calculus, the concept of a limit is a fundamental building block that underpins many other concepts such as continuity, differentiation, and integration. When we talk about the limit of a function as ( x ) approaches infinity, we are discussing the behavior of the function as ( x ) grows without bound.

Formal Definition

The formal definition of a limit as ( x ) approaches infinity is given as follows:

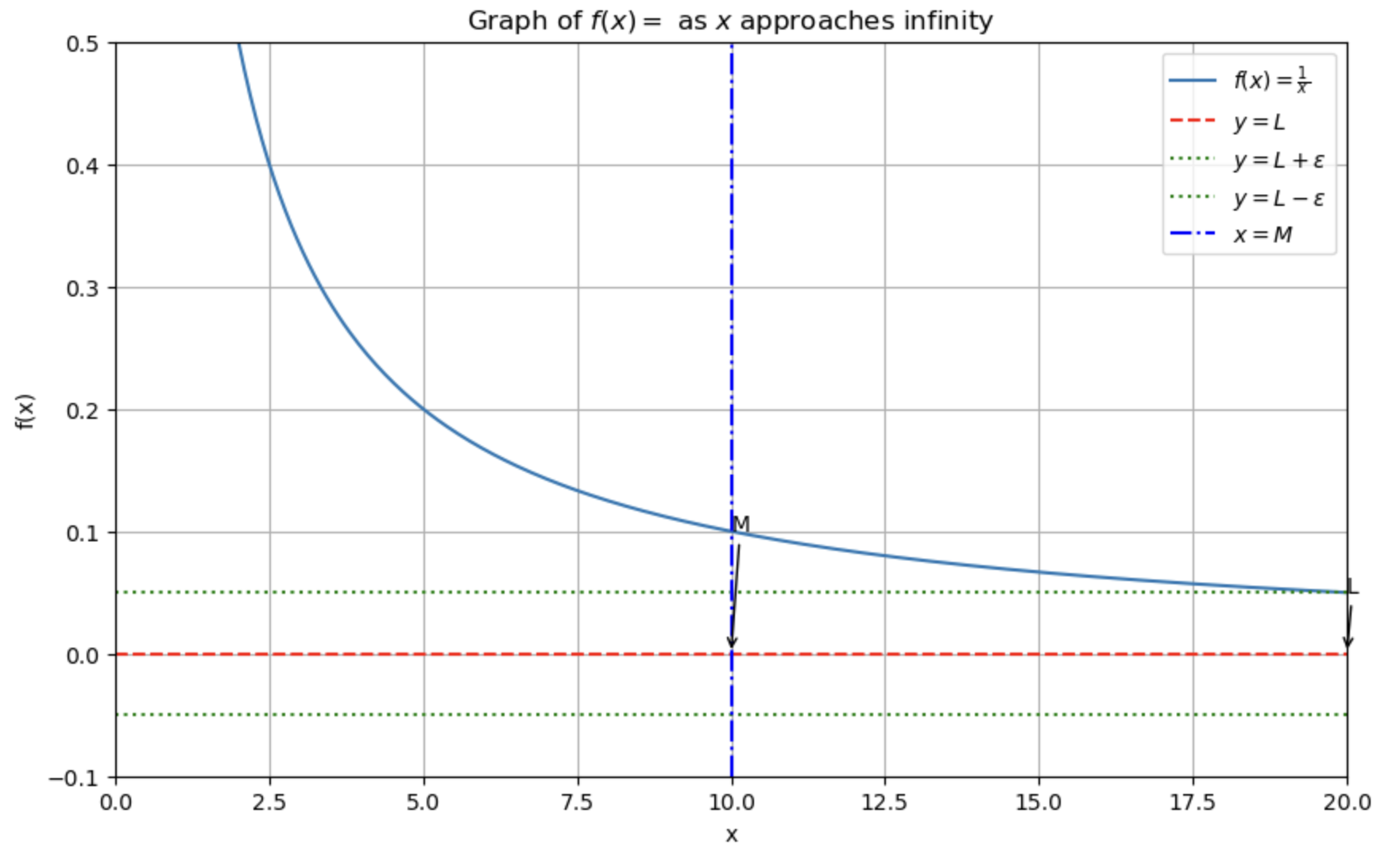

For a given function ( f(x) ), we say that the limit of ( f(x) ) as ( x ) approaches infinity is ( L ) if for every real number ( \varepsilon > 0 ), there exists a real number ( M ) such that for all ( x > M ), the absolute difference between ( f(x) ) and ( L ) is less than ( \varepsilon ). In mathematical notation, this is expressed as:

Interpretation

This definition encapsulates the idea that as ( x ) becomes arbitrarily large, the function ( f(x) ) approaches the value ( L ). The variable ( \varepsilon ) represents how close we want ( f(x) ) to be to ( L ), and ( M ) represents a point beyond which all function values ( f(x) ) are within ( \varepsilon ) of ( L ).

Python Code

Questions

Question 1

Prove ( \lim_{{x \to 3}} (2x + 1) = 7 )

To prove the statement ( \lim_{{x \to 3}} (2x + 1) = 7 ) using the epsilon-delta definition, we need to show that for every ( \varepsilon > 0 ), there exists a ( \delta > 0 ) such that if ( 0 < |x - 3| < \delta ), then ( |(2x + 1) - 7| < \varepsilon ).

Let's breakdown the steps:

Expression Simplification: Simplify the expression ( |(2x + 1) - 7| ): [ |(2x + 1) - 7| = |2x - 6| = 2|x - 3| ]

Epsilon-Delta Relation: Now, we need to find a ( \delta ) such that ( 2|x - 3| < \varepsilon ) whenever ( 0 < |x - 3| < \delta ). It's clear from the expression that if we choose ( \delta = \frac{\varepsilon}{2} ), the inequality will be satisfied: [ 2|x - 3| < \varepsilon ]

Formal Proof: For every ( \varepsilon > 0 ), choose ( \delta = \frac{\varepsilon}{2} ). Then, for ( 0 < |x - 3| < \delta ), we have: [ |(2x + 1) - 7| = 2|x - 3| < 2\delta = \varepsilon ]

Therefore, by the epsilon-delta definition of a limit, we have proved that: [ \lim_{{x \to 3}} (2x + 1) = 7 ]

Intuition

Question 2

Prove that: [ \lim_{{x \to 1}} x^2 + 5x + 6 = 12 ] using the formal epsilon-delta definition of a limit.

Step 1: Plug the Limit Point into the Function

First, we plug ( x = 1 ) into the function ( f(x) = x^2 + 5x + 6 ) to find the limit ( L ):

[ f(1) = 1^2 + 5(1) + 6 = 1 + 5 + 6 = 12 ]

Step 2: Set Up the Epsilon-Delta Definition

According to the epsilon-delta definition of a limit, for every ( \varepsilon > 0 ), there exists a ( \delta > 0 ) such that if ( 0 < |x - 1| < \delta ), then ( |f(x) - 12| < \varepsilon ).

Step 3: Simplify the Expression for ( |f(x) - 12| )

[ |f(x) - 12| = |x^2 + 5x + 6 - 12| = |x^2 + 5x - 6| ]

Step 4: Factor the Quadratic Expression

[ x^2 + 5x - 6 = (x - 1)(x + 6) ]

Step 5: Substitute the Factored Expression Back into the Absolute Value Expression

[ |f(x) - 12| = |(x - 1)(x + 6)| ]

Step 6: Find an Expression for ( \delta ) in Terms of ( \varepsilon )

We want to find a ( \delta ) so that ( |(x - 1)(x + 6)| < \varepsilon ) whenever ( 0 < |x - 1| < \delta ).

This is a bit tricky, but one way to approach this is to bound the expression ( |x + 6| ). If we restrict ( \delta ) to be less than or equal to 1, for example, then ( x ) will be between 0 and 2. In that case, ( |x + 6| ) will be between 6 and 8.

Step 7: Set Up the Inequality [ |(x - 1)(x + 6)| < \varepsilon ] [ |x - 1| |x + 6| < \varepsilon ]

Now, we can bound ( |x + 6| ) by 8 (the larger value) to ensure the inequality holds: [ |x - 1| \cdot 8 < \varepsilon ]

Now, solve for ( |x - 1| ): [ |x - 1| < \frac{\varepsilon}{8} ]

Step 8: Choose ( \delta )

Now we can choose ( \delta = \min\left(1, \frac{\varepsilon}{8}\right) ). This choice of ( \delta ) ensures that the inequality ( |f(x) - 12| < \varepsilon ) holds whenever ( 0 < |x - 1| < \delta ).

Conclusion:

We have demonstrated that for every ( \varepsilon > 0 ), there exists a ( \delta > 0 ) (specifically, ( \delta = \min\left(1, \frac{\varepsilon}{8}\right) )) such that if ( 0 < |x - 1| < \delta ), then ( |f(x) - 12| < \varepsilon ). Hence, by the epsilon-delta definition of a limit, ( \lim_{{x \to 1}} x^2 + 5x + 6 = 12 ).

Question 3

Prove that this limit does not exist:

Proof:

Objective: We want to show that the function ( \cos(\pi x) ) does not have a limit as ( x ) approaches infinity.

1. Speculating a Potential Limit ( L ):

This means we're thinking of any conceivable real number ( L ) as the possible limit of ( \cos(\pi x) ) as ( x ) goes to infinity. But, we're going to show that no such ( L ) can exist.

2. Defining a Small Positive Deviation ( \varepsilon ):

The ( \varepsilon ) is a "buffer" we introduce. We're going to argue that ( \cos(\pi x) ) can always deviate from the speculated limit ( L ) by at least this amount, regardless of how large ( x ) is.

3. Two Clear Cases Based on ( L ): Let's discuss the nature of ( \cos(\pi x) ). It only has two possible values when ( x ) is an integer:

- 1 (for even values of ( x ))

- -1 (for odd values of ( x ))

Given this behavior, we divide our analysis into two straightforward cases based on the value of ( L ):

Case A: ( L ) is Non-negative (i.e., ( L \geq 0 ): If ( L ) is either positive or zero, then consider any odd ( x ). For such ( x ), ( \cos(\pi x) = -1 ). Hence:

Since ( L \geq 0 ), the absolute value ( |-1 - L| ) is greater than 1. This is more than our ( \varepsilon ) buffer, meaning our function deviated from ( L ) more than we allowed.

Case B: ( L ) is Negative (i.e., ( L < 0 ): Now, if ( L ) is negative, consider any even ( x ). For such ( x ), ( \cos(\pi x) = 1 ). This leads to:

Because ( L ) is negative, the absolute value ( |1 - L| ) is again greater than 1. Our function has once more deviated from ( L ) more than the ( \varepsilon ) buffer permits.

Conclusion: Regardless of the value of ( L ) (whether it's positive, negative, or zero), the function ( \cos(\pi x) ) can always deviate from it by more than ( \varepsilon = \frac{1}{2} ) for some integer ( x ). This demonstrates that ( \cos(\pi x) ) does not have a limit as ( x ) approaches infinity.

In essence, the oscillatory behavior of ( \cos(\pi x) ) between 1 and -1 is leveraged to argue that no real number can serve as its limit as ( x ) goes to infinity.